In the immediate aftermath of the February 6 earthquake in Turkey, journalist Yüsra Batıhan traveled to Elbistan, one of the hardest-hit areas. Over the course of a month, Batıhan, then working for Mezopotamya News Agency, reported on relief efforts, witnessing the struggles of children and women through a unique lens as a female journalist. However, her mental resilience was tested, and her social media posts led to an investigation under the controversial "Censorship Law."

Reflecting on her experience, Batıhan described the emotional toll of covering the disaster. "In the field, journalists often do more than just report. You sit and cry with people, and sometimes you become the one delivering humanitarian aid," she said. Her experiences in Elbistan and Hatay, both severely affected by the earthquake, highlight the intense emotional strain of working in such an environment.

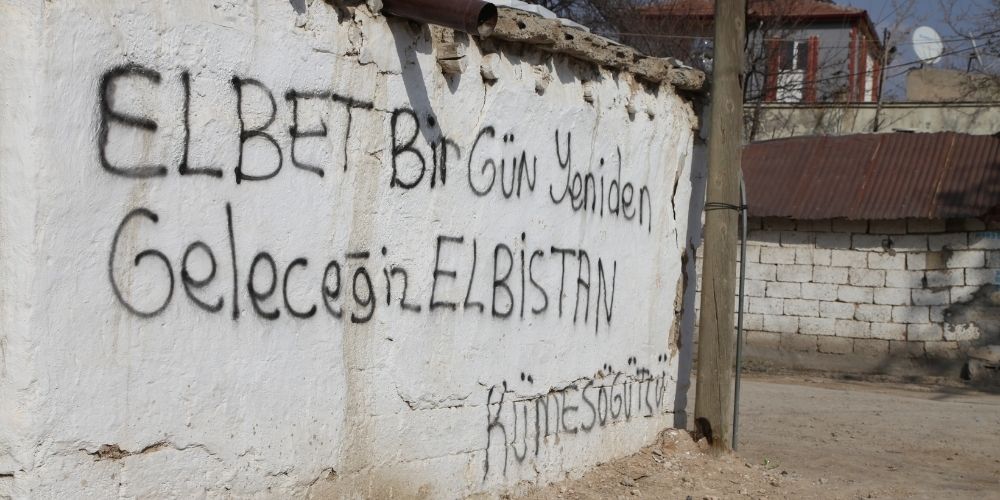

In the days following the quake, Batıhan worked from the capital, Ankara, where she felt a deep frustration at being unable to go to the disaster zone. She eventually convinced her editor to send her to the region, arriving in Kahramanmaraş on February 17, and then Elbistan on February 18. Once there, she quickly realized that staying mentally strong was the hardest challenge. She encountered domestic violence victims in tents, displaced refugees, and survivors struggling without even basic necessities like blankets.

One of the most shocking moments came when Batıhan learned that entire families in Elbistan's villages had been struck by cancer, with a local cemetery even nicknamed "Canceristan." She described meeting a cancer patient who, due to disability, asked his family to leave him behind to fend for themselves. These encounters, especially with elderly people shuffled between shelters, often brought her to tears.

During her time in the region, Batıhan came to understand the vital role of female journalists in disaster zones. She explained how women survivors began to seek her out, sharing their stories and forming a support network. "Women felt more comfortable confiding in me, which created a sense of trust and solidarity. I realized how important it was for women to have someone they could talk to," Batıhan said.

Despite her reporting efforts, Batıhan faced challenges, especially when trying to access aid camps, where she was often expelled by security. Her press credentials from her agency were not recognized, and because she did not hold the government-issued "turquoise press card," she was sometimes barred from entry. This made it difficult for her to reach vulnerable groups like refugees and women.

Batıhan's work also led to legal troubles. After returning from Elbistan, she was investigated for allegedly spreading false information under Turkey's new disinformation law, a controversial measure that has been criticized for curbing press freedom. The charges stemmed from her social media posts during the quake, even though the news stories she had published contained the same information.

Another journalist, freelance photojournalist Efekan Akyüz, shared his experiences covering the disaster in Hatay. He arrived in the region on the first day after the earthquake and faced multiple challenges, from navigating collapsed roads to enduring days without proper food or shelter. "We spent the first few nights sleeping in the car or with those keeping vigil over the rubble," Akyüz said. His work was interrupted when he injured his foot while covering a false alarm about a dam break in Antakya.

A year after the disaster, Batıhan continued to report on the long-term impacts. In Hatay, rubble still littered the streets, and many people were still living in tents. "After so many interviews, people no longer wanted to talk. They were exhausted," she said, describing how the situation in the region remained dire. Many of the roads were still impassable, and she relied on other journalists for help navigating the area.

Despite the difficulties, Batıhan emphasized that the solidarity among journalists in the disaster zone helped keep the stories of survivors alive. "Without this support, it would have been impossible to reach many of the affected areas," she said, reflecting on the unique challenges faced by journalists trying to document one of Turkey's deadliest disasters in recent history.