The Article 217/A, which came into effect in Turkey in late 2022, has become known to the public as the "censorship law" and has raised serious concerns regarding freedom of expression. Criticized for its vague definitions and broad scope for interpretation, this law was particularly used as a tool of pressure on journalists and social media users following the February 2023 earthquake. Many individuals advocating for the public's right to access information faced investigations, detentions, and lawsuits, further deepening fear and self-censorship in society. As the Media and Law Studies Association (MLSA), we have launched the Censorship Law Series, which examines the implementation of this law, its societal impact, and its consequences on freedom of expression with contributions from journalists.

Rabia Çetin

Since Turkey’s Disinformation Law came into effect on Oct. 18, 2022, journalists have increasingly become its primary target. Reporters told the Media and Law Studies Association (MLSA) that the law is being used to suppress corruption investigations, with complaints coming from various political factions—both government and opposition.

One of the journalists facing multiple investigations for her corruption reporting is Aslıhan Gençay.

In December 2024, two separate investigations were launched against Gençay over her reports on corruption allegations involving former opposition Republican People's Party (CHP) mayor Lütfü Savaş and the Hatay Metropolitan Municipality. The following month, in January 2025, another investigation was opened against her for reporting on similar allegations related to former Samandağ Mayor Refik Eryılmaz, also from CHP. Gençay had to give statements on consecutive days and submitted documents supporting her reports.

From threats to criminal complaints

Gençay described the Disinformation Law as a tool of intimidation used by "power centers, regardless of party affiliation." Despite facing legal pressure, she remained defiant: “No matter how many investigations are opened, I will continue to report on corruption.”

She detailed her experience:

"Ahead of the 2024 local elections, I reported on corruption in six municipalities, including Hatay Metropolitan Municipality. After publishing my report on Hatay, I started receiving a flood of complaints from the public regarding other municipalities. Among these complaints were allegations about Refik Eryılmaz, the former mayor of Samandağ. I confirmed the claims using three to four sources and published my findings. Afterward, Eryılmaz pressured me—he called, threatened me, and posted defamatory comments on the websites I write for. A member of the municipal council even messaged me, offering to take me to Samandağ so I could write ‘the truth.’

When the corruption allegations gained traction, CHP held a primary election in Samandağ, and Eryılmaz lost, failing to secure his candidacy. He blamed my reporting for his defeat and filed a criminal complaint against me on behalf of the municipality. I later met with the current mayor, who confirmed that inspectors were being sent to investigate corruption within the municipality. However, instead of waiting for the results of this probe, Eryılmaz rushed to file a complaint against me in the name of the municipality."

Gençay said she faced a similar backlash from former Hatay Metropolitan Mayor Lütfü Savaş: "I received threats like ‘Swear loyalty to our mayor, Lütfü Savaş.’ When those didn’t work, they filed a criminal complaint. Even though I presented solid evidence of corruption, I am being charged with ‘spreading misleading information to the public.’"

She pointed out that following her reporting on corruption at the Hatay Water and Sewerage Administration (HATSU), investigators launched a probe into 36 individuals. “My reports were proven correct, yet I am still under investigation,” she added.

‘Journalists have no space left to breathe’

Gençay stressed that the Disinformation Law, drafted by the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and its far-right ally Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), is not solely being used by those in power: “It has become a tool for all power centers, regardless of political party, to threaten journalists.”

"Whether it's the government, the state, or local authorities—whoever you report on, they weaponize this law and the judiciary against you. It’s not just AKP; CHP municipalities and individuals are also benefiting from it. Wherever there is a power center, journalists face this issue. It doesn’t matter if it’s a political party, a company, or a local government.

This law must be repealed. Journalists have no space left to breathe, and this country needs fresh air. They may use this law to open investigations against us, but they will not stop us. I will continue reporting on corruption."

‘When we expose government-linked corruption, we face judicial threats’

Evren Demirdaş, a journalist for Sözcü, has also been repeatedly investigated for reporting on corruption involving figures close to the government.

"When we report on corruption in public tenders involving people close to the government, the response is always a legal threat," Demirdaş said.

In one instance, Demirdaş reported on Oct. 13, 2024, that a businessman affiliated with AKP, Veysel Demirci, was awarded a 642 million lira ($22 million) contract from Turkey’s public housing authority (TOKİ). On Nov. 2, he was charged under the Disinformation Law with "publicly spreading misleading information."

Later that month, he was investigated again for reporting on a tender awarded without competitive bidding by Elazığ’s Special Provincial Administration, which falls under the governor’s office. His report, headlined “Governor cites ‘security concerns’ to justify awarding a multimillion-lira contract through negotiations”, led to another investigation under the same law.

‘The law is being used as a weapon against journalists’

"The judiciary is being used as a weapon, and journalists are treated as targets," said Demirdaş. "The Disinformation Law leads to self-censorship, particularly in local media. Despite the legal threats, we must continue exposing corruption and bringing the truth to light."

He described the law as an "obstacle to journalism," saying, "Those who file complaints against journalists often know the cases will be dismissed. But they do it anyway, just to intimidate us."

‘A landmine planted under freedom of expression’

According to MLSA data, in the two years since the Disinformation Law was enacted, 56 journalists, writers, and media workers have been subjected to 66 investigations. Meanwhile, Turkey’s Justice Committee reported that, under the same law, prosecutors have opened 4,590 investigations and 384 lawsuits.

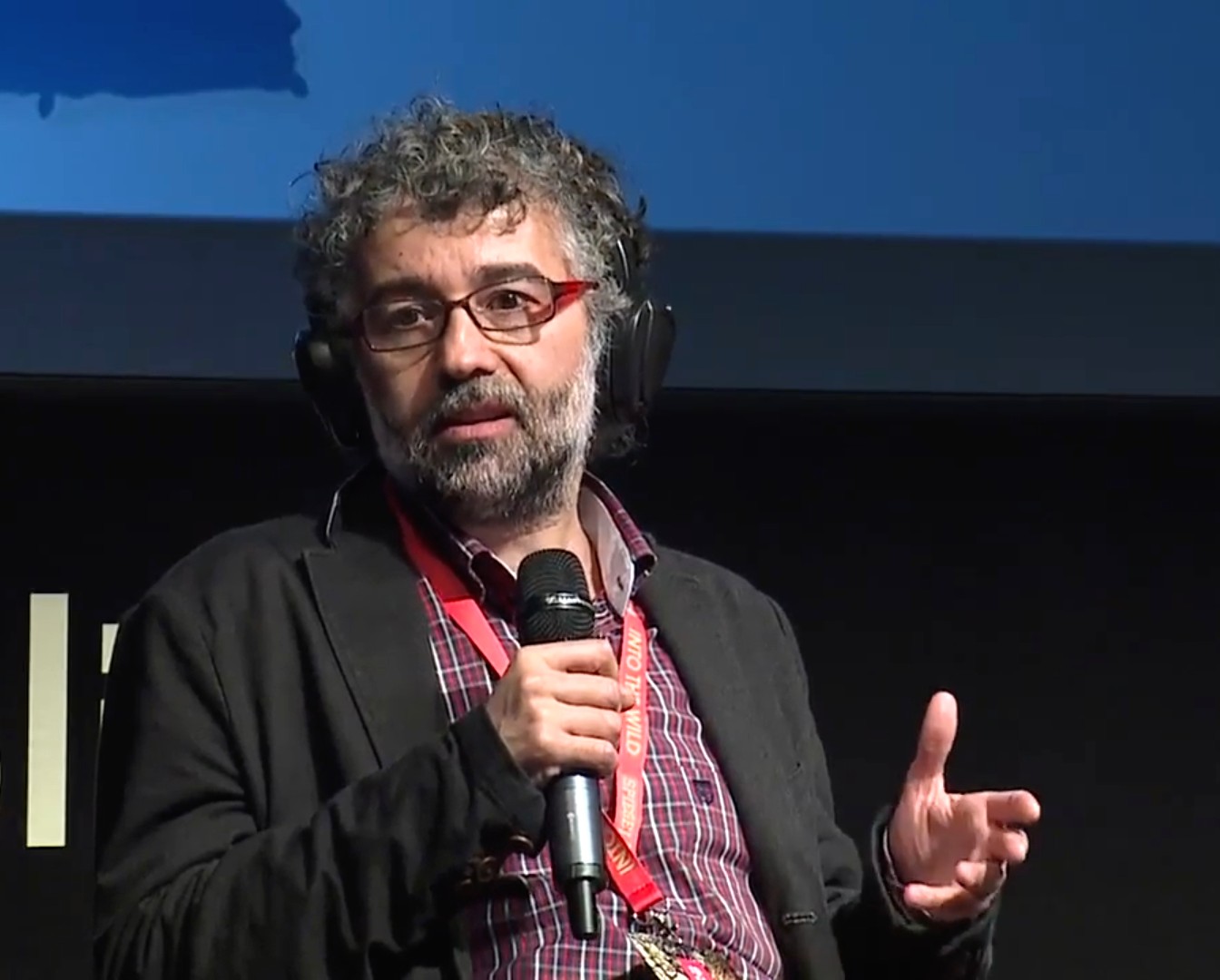

Erol Önderoğlu, the Turkey representative for Reporters Without Borders (RSF), described the law as "one of the last landmines placed under freedom of expression."

"The Disinformation Law has unfortunately become a judicial harassment tool, as evidenced by the arbitrary investigations and prosecutions against journalists," said Önderoğlu.

"The government had promised that this law would only be used in cases of ‘widespread social panic,’ but we have seen it arbitrarily applied against local journalists and investigative reporters like Tolga Şardan, who dig into cases that make authorities uncomfortable."

Önderoğlu criticized the law for shifting the burden onto journalists to prove their reports in court instead of allowing for open public discourse: "Instead of ensuring journalists have access to accurate information in the first place, they are now forced to prove the truth in court. This only happens in societies where democracy is not functioning properly."

"Many journalists are acquitted after submitting their evidence in court. However, in authoritarian-leaning regimes, laws meant to promote information transparency are repurposed to silence journalists. Unfortunately, this is what we are witnessing in Turkey today," he concluded.