32 years since the murder of Musa Anter, justice remains elusive

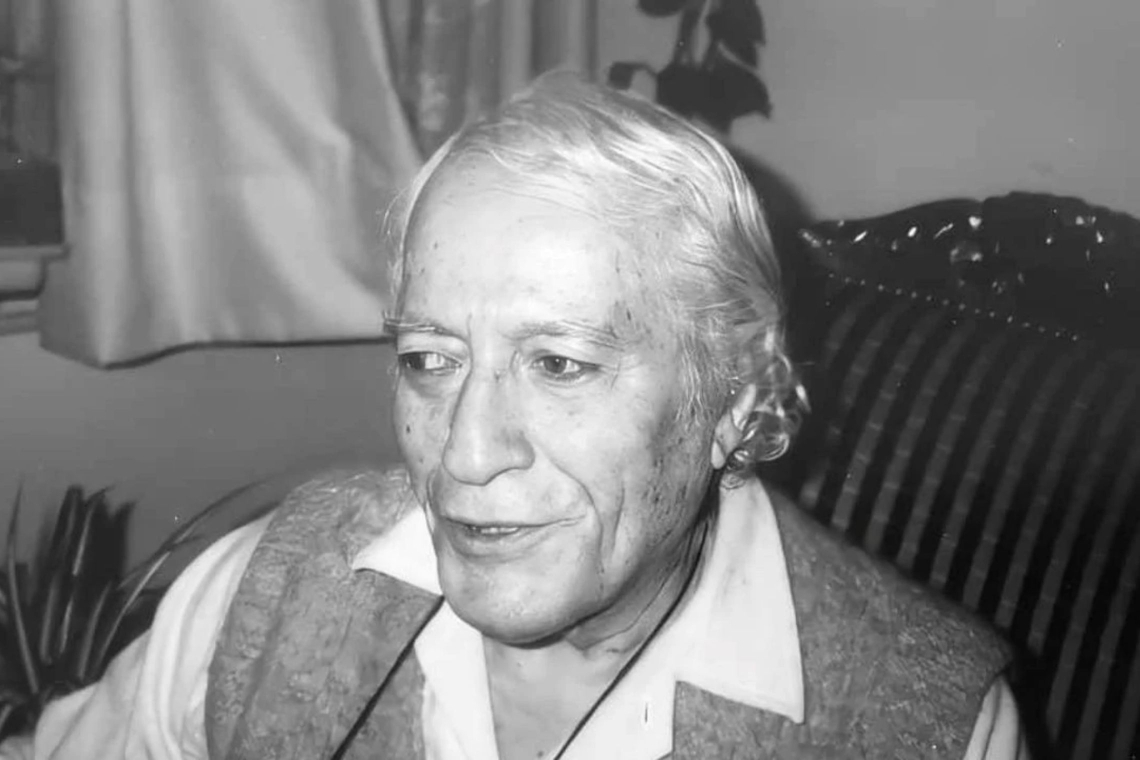

It has been 32 years since the assassination of journalist and writer Musa Anter, a prominent figure in Kurdish journalism, yet the case remains unresolved despite confessions and substantial evidence. Anter, a columnist for Özgür Gündem, spent 11.5 years in prison due to his writings and ideas. His case was closed with a statute of limitations ruling, leaving many unanswered questions and obscuring well-known truths.

Anter was murdered in Diyarbakır on September 20, 1992, while attending a cultural festival. Just 38 days prior, he had written a poignant article in Özgür Gündem about his nephew, Hüseyin Deniz, who had also been killed. Anter wrote, “Son, I can’t say you’re dead. It feels as if saying you’ve died would mean I killed you. Don’t worry, I’ll keep writing in your place as long as I live. If they kill me too, it’ll be a beautiful reunion.” His words tragically foreshadowed his own assassination.

Although the Diyarbakır State Security Court opened an investigation, the case remained unsolved for years. The 1997 Susurluk Report, prepared by Prime Ministry Inspector Kutlu Savaş at the request of then-Prime Minister Mesut Yılmaz, linked Anter’s murder to “Yeşil” (Mahmut Yıldırım), a notorious figure involved in extrajudicial killings.

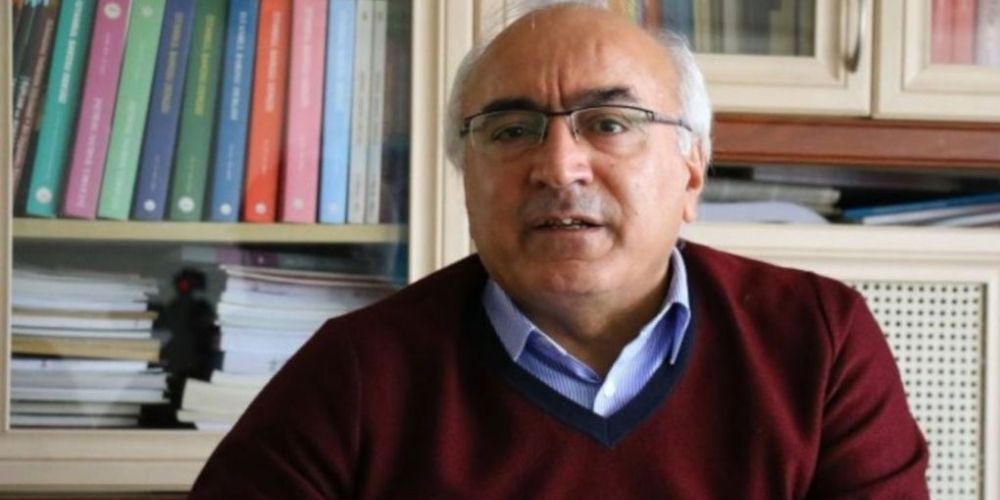

Despite the confessions and reports, those responsible for Anter’s murder have never been held accountable. Öztürk Türkdoğan, a prominent human rights advocate, emphasized that the murder should be classified as a crime against humanity, thus preventing it from being dismissed due to the statute of limitations.

Confessions published by journalists lead to prosecution

In 2004, former informant Abdülkadir Aygan, living in Sweden, confessed to being part of the JİTEM team responsible for Anter’s assassination. His confession, published by Ülkede Özgür Gündem under the headline "Here is the team that killed Apê Musa," named Mahmut Yıldırım as the mastermind behind the plot. However, instead of leading to accountability, the publication resulted in a lawsuit against the newspaper’s owner and editor-in-chief.

European Court of Human Rights rules against Turkey

When the investigation into Anter’s murder made no progress, the case was brought to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). In 2006, the ECHR ruled that there was substantial evidence suggesting that state officials were aware of the plot and that the Turkish government had failed to conduct an effective investigation. Turkey was ordered to pay compensation.

Case opened just two months before statute of limitations deadline

In 2013, 21 years after the murder, the Diyarbakır Special Prosecutor's Office reopened the case based on Aygan’s confession, just two months before the statute of limitations expired. Arrest warrants were issued for JİTEM members Cemil Işık, Ali Ozansoy, Hamit Yıldırım, and Mahmut Yıldırım (code-named “Yeşil”). Hamit Yıldırım was arrested in June 2012, but efforts to extradite Aygan from Sweden failed.

Despite these developments, the trial languished. In 2015, it was moved from Diyarbakır to Ankara for “security” reasons and merged with another JİTEM case. The increasing number of defendants and the inability to capture fugitive suspects, along with the failure to obtain Aygan’s testimony, delayed the case further. Despite requests from Anter’s family lawyers to separate the murder case from the broader JİTEM trial, the Ankara 6th High Criminal Court rejected these motions.

Case dismissed due to statute of limitations

In a decision handed down on September 21, 2022, just one day after the 30th anniversary of Anter’s murder, the court dismissed the case due to the expiration of the 30-year statute of limitations under Turkey’s previous penal code. The JİTEM trial continues separately, but the Anter family’s legal team has appealed the dismissal to higher courts, including the Constitutional Court. No ruling has been made in the two years since the appeal.

Human rights advocate Öztürk Türkdoğan, who has followed the case since the beginning, highlighted that journalists were targeted in the 1990s for exposing the violence and political assassinations aimed at silencing the Kurdish population. “The aim of the political killings of that period was to intimidate the Kurdish people and prevent the Kurdish issue from being discussed,” Türkdoğan stated.

“Perpetrators never absolved in the public’s conscience”

Despite the court's dismissal, Türkdoğan emphasized that the case files and parliamentary reports clearly show that Anter was killed by JİTEM, an illegal counterterrorism unit tied to the state. He criticized the state’s strategy of using statute of limitations laws to evade responsibility. “This is impunity. The state has always followed the tactic of delaying investigations and trials in these cases,” he said, adding that the perpetrators remain condemned in the public’s conscience, even if they escape legal punishment.

Lack of reckoning with the past raises concerns for the future

Türkdoğan also warned that without confronting these past crimes, there is no guarantee that such human rights violations will not occur again. He urged Turkey to face its history and open a new chapter by ensuring justice for the crimes of the 1990s, including Anter’s murder. “We are pushing for the statute of limitations dismissal to be overturned and the trial to continue,” Türkdoğan stated, pledging to pursue every legal avenue.

Impunity persists for 1990s crimes

Attorney Esra Kılıç, of the Truth Justice Memory Center’s legal program, said the dismissal of cases like Anter’s reflects a broader pattern of impunity for crimes committed in the 1990s. At least 12 high-profile cases related to unsolved murders and extrajudicial killings were opened after the year 2000, but most ended in acquittals or were dropped due to the statute of limitations. Only the Yüksekova case is ongoing, while others, like the Ankara JİTEM, Cizre, and Lice cases, have been closed.

Kılıç identified several legal obstacles contributing to impunity, including treating enforced disappearances as simple homicides subject to standard limitation periods, transferring cases away from the areas where the crimes occurred, and failing to investigate the broader structures behind the crimes. Additionally, the European Court’s rulings are often ignored, and public institutions frequently obstruct investigations.