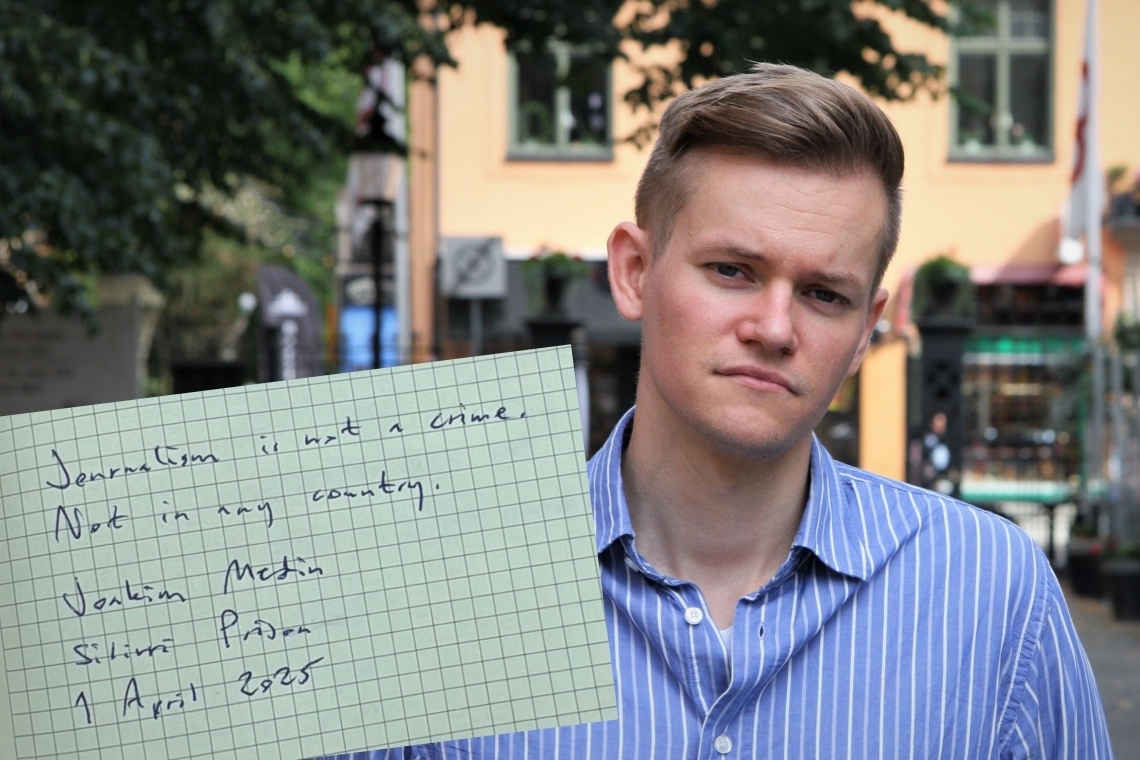

Joakim Medin, a Swedish journalist detained in Turkey, sent a message from Silivri Prison declaring, “Journalism is not a crime. Not in any country.” Medin, a foreign correspondent for the Sweden-based newspaper Dagens ETC, was arrested in Istanbul on March 28 as part of an ongoing investigation.

Medin’s message, shared in both English and Swedish through his lawyers, came after a visit by Attorney Batıkan Erkoç from the Media and Law Studies Association (MLSA) on April 1. According to Erkoç, Medin is in good health and high spirits.

Medin was detained at Istanbul Airport on March 27 upon arrival from Budapest. According to his own account, shared with lawyers on March 29 at Maltepe Prison, Turkish police stopped him during passport control and took him into custody. His phone was confiscated, and he was informed that he was being sought in connection with alleged ties to the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and its umbrella organization KCK, both designated as terrorist groups by Turkey, the U.S., and the EU.

During his interrogation, Medin said no interpreter or lawyer was present. Instead, police officers used Google Translate to communicate. When he refused to sign a document he couldn’t understand, officers signed it on his behalf and did not provide him with a copy.

Later that day, around 4 p.m., Medin was transferred to the Airport Police Station with other detainees. He reported that basic needs such as food, water, and access to a toilet were not provided. He was taken for medical checks twice, but both were conducted briefly in a conference room in front of civilians rather than in a hospital setting.

On the morning of March 28, Medin received a list of lawyers suggested by the Swedish consulate. However, after those lawyers proved unreachable, an attorney from the Ankara Bar Association was appointed.

That same day, Medin testified via video conferencing system SEGBIS before a prosecutor. He was formally charged with “insulting the President,” “membership in a terrorist organization,” and “spreading terrorist propaganda.” The terrorism propaganda charge was later dropped during the legal proceedings.

In court, Medin was asked whether he had participated in a protest in Stockholm where an effigy of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was displayed. Medin denied taking part in the protest, stating he had only shared posts on social media in his capacity as a journalist.

On March 30, Turkey’s Presidential Communications Directorate’s Center for Combating Disinformation issued a statement asserting that Medin was not arrested for journalistic activity. However, during his interrogation, police questioned him about his reporting from Syria, photos taken during news assignments, and posts shared on social media. Medin, who has been working as a journalist since 2009, said he has covered conflicts in both the Middle East and Europe. When asked about a photo showing him with a flag of the Kurdish PYD/YPG, groups associated with the Syrian branch of the PKK, Medin explained, “I didn’t take the photo. Someone who was there at the time handed me the flag.”

Prosecutors also accused Medin not only of reporting on protests but of organizing them. When he was brought before the court, the proceedings lasted only three minutes. He was then formally arrested on charges of “insulting the President” and “membership in a terrorist organization,” and sent to Maltepe Type L Prison in Istanbul.

Medin was initially held in solitary confinement. His lawyer, who visited Maltepe Prison on March 30, discovered that he had been transferred to Silivri Prison, a high-security facility outside Istanbul that has frequently housed political prisoners and journalists. During the April 1 visit, Medin said he feared his lawyers might have difficulty locating him due to the sudden transfer.

Silivri Prison, located west of Istanbul, has become symbolic of Turkey’s crackdown on dissent, particularly since the 2016 failed coup attempt. The Swedish journalist’s detention has drawn concern from press freedom advocates, amid growing international scrutiny of Turkey’s treatment of foreign journalists.